Last January, Marcus and I climbed for a month in the Cascades. I started writing something about it a few times, but didn’t end up with much because we didn’t really climb much of anything, bumbling from alpine failure to alpine failure. A bummer at the time, but we apparently learned a thing or two because there was a success or two among this year’s failures.

“Yup, yup, yes,” Marcus says as the car slides forward at an off-trajectory angle. The packed slush-snow is deeper than the wheel tracks of my lifted Subaru and we swim down the road on the brink of control. And then, we don’t. I watch the RPM needle flatline as the engine dies and we slide to a stop in the middle of Cascade River road. I arrived prepared for this eventuality, but my heart still dropped with the tachometer. Shit.

Fourteen months ago I found myself driving down the same road in the same car with the same white knuckles. Knowing the consequences of getting the car stuck this deep in the mountains, we stopped seven miles from the trailhead for our objective, Eldorado Peak, and skied seven miles of snowy road to start the climb. We quickly realized we didn’t have enough food, days, and endurance to push through the deep snow to make it to the summit and skied back to the car the next day.

This year, Marcus and I were back for revenge. We doubled the time on our self-register permit, dialed in our approach ski setups, and loaded four days worth of food. Last year’s failure had been hilarious, but still stung a bit. Eldorado was easy. We had both climbed it in a matter of hours in the summer and it was climbed in winter fairly frequently. With another year’s climbing experience on our side, our grudge match was sure to be successful.

At least, until the car died.

The green mile post marker next to the dead Subaru mocked us: MP7, seven miles farther from the trailhead than we got last year. It was late afternoon and after trying everything I could think of on the car and still hearing the ching-ching-ching of an engine turning over with no combustion, we accepted our fate and skied in anyway.

We made it seven miles the first night and quickly realized we wouldn’t have made it much farther in the car anyway. The snow was deep, deeper than last year, which had been a banner snowpack year for the Cascades. Winter climbing in the Cascades is notoriously difficult in a normal season, and more so now. This is where the, “it’s all training,” philosophy comes in handy.

Rain saturates our single-walled alpine bivy tent. The tiny tent is awesome when it’s freezing and snowing, but above 32º it’s like wearing a windbreaker in a rainstorm: cold and wet. Waking up in a snow pit, in the rain, in the middle of a road and knowing you haven’t even started the real approach to an alpine route isn’t the best moral booster ever. Still, we managed to pack our bags the next morning and make it to the real start of the climb before noon.

The trail to the Eldorado glacier is infamous in the Cascades climbing community for being thickly vegetated and very steep — in the summer. In the winter it’s one of two evils: waist deep postholing up a 45º slope or steep bushwhacking on skis. We chose the latter, which could’ve been the wrong choice. The uphill ski took four times as long as the hike did in bare conditions.

Rockfall and wet slides boomed down the slope ahead and Marcus and I sat silently on our packs, finally above treeline. We timed our approach in the hopes of catching the route itself — the NW Ice Couloir — on the one-day weather window in the forecast. This meant that the two days before we would travel in the rain to a base camp while the freezing level was high and climb the route after the freezing level had dropped back down, clearing the skies and hardening up the snowpack.

In spite of the forecast, it was still raining. We thought that conditions on our attempt last year were the worst they could get, but we were wrong. We were still soaked. Things still sucked. And despite better equipment, better fitness, and better mental preparation, we decided to bail a few hundred feet below our turnaround point on last year’s attempt.

Climbing is fun. I look forward to it. Despite this, whenever a decision to bail is reached, especially for good reasons, I always feel giddy and relieved. Sitting on our packs in the rain, we laughed like idiots and ate as much of our food as we could. And we headed back down.

At the trailhead — still 13 miles of skiing away from the dead car — there’s a small USFS toilet. The smelly, hole-in-the-ground kind. A small roof poked out in front of the door to make a 4’x6’ slab of snow-free concrete surrounded by 3’ snow walls. Compared to our soaked alpine tent, this felt like a hotel master suite and with no reservations we setup camp on the porch of the shitter.

With heavy rain, a temperature hovering in the mid-30s, and soaked everything, hypothermia conditions were prime. I laid down for the night suspecting I wasn’t going to sleep much, and fifteen minutes later I accepted the reality that my soaked sleeping bag offered no insulating value and chucked it into a sopping pile next to me. I didn’t sleep at all, spending most of the night forcing myself to eat, doing sit-ups on my pad, and reboiling a hot water bottle to keep my core temps in the safe zone. At some point in the night we realized it would be warmer inside the shitter, and with very little shame made it our home. Somewhere around now we realize we have moved into the ‘Spectacular Failure’ zone, and more laughs were had.

The rain doesn’t let up the next day, and at noon we resign ourselves to skiing the 13 miles back to the car in the downpour. It’s a massive relief to arrive at the car in the dark that night to find it still there, though the small hope I held in my heart that it would now start was immediately crushed by the ching-ching-ching that greeted my anxious key-turning. Type-2 fun.

The car did mean a propane stove and real food, and with no hesitation we pitched a table in the middle of Cascade River Road at MP7 and Marcus cooked a giant pan of Huevos Rancheros. I slept in a warm, dry sleeping bag in my car. Marcus pitched his alpine tent in the middle of the road, and woke up soaked again — this time quite literally floating on his sleeping pad inside the tent. The morning brought our next reservation: walking the eight miles back to the closest cell service.

Eight road miles in running shoes was a dream compared to the 28 or so slush miles we had done on skis in mountaineering boots over the last few days. We nearly skipped down the road to the Chevron station in Marblemount. We convinced a tow truck driver to drive a bit of snowy road and got the aging Subaru to an auto shop in Sedro Wooley just before they closed, settling in to the first dry night of the last four in a budget motel.

With healed egos, automobile, and bodies, we headed to Snoqualmie Pass a few days later for a two-day weather window. The first day we climbed the South Gully on Guye Peak with a leisurely 12 noon start. We accessed the peak from a parking area right off the interstate, putting on skis literally under an I-90 overpass — popping boots into ski bindings while semi-trucks boomed overhead isn’t a feeling I’ll soon forget. We soloed most of the route, roping up for one mixed pitch near the top and disaster-skiing down a snowshoe track on the descent. The easy route wasn’t much of a climbing accomplishment, but not failing on something was still a soothing ego-balm.

Both of us had been wanting to do a classic route called the NY Gully on Mount Snoqualmie, and with the melt-freeze cycles of the past week the chances of it being in shape were good. Marcus lead the first half, stretching the rope through most of the famous box gully pitch, which was a bit thin but still yielded satisfying Scottish-stye frozen turf sticks. This day the forecast was dead-on and at precisely eleven the sky started spitting snow in time for my lead block, which took us through the rest of the gully and to the summit plateau. We both managed to free the crux A2 section of the route with a gloved hand-to-fist jam sequence. This felt pretty rad: having seen many photos of the aid section online, I always thought it looked free climbable and we were both psyched that it was.

The descent was pleasant plunge-stepping all the way to the massive Phantom Slide avalanche path. In solid snow conditions, the massive slide path makes for a wicked glissade. We dropped almost 1000 feet of vert in twenty minutes and arrived back at the car 9.5 hours after we left that morning. Doing one of the most difficult grade IV alpine routes in the area in under ten hours was a nice consolation for our Spectacular Failure on Eldorado and gave us hope that maybe we were doing something right after all.

After zero on-route successes last year, our single success on NY Gully was satisfying enough that we decided to cash the last weather window of the trip in on an uncertain objective: unclimbed lines on the SW face of Sloan Peak. Friends of Marcus had graciously offered to give us a place to crash, and a day after climbing at Snoqualmie we found ourselves sitting in front of a wood stove in a yurt in Rockport, resting and scouring photos of the nearby Sloan Peak.

Winter climbing in the Cascades saw a huge boom in the early 2000s with the advent of two things: CascadeClimbers.com, an internet forum that popularized the phenomenon of ‘Trip Reports,’ which gave people instant access to current climbing conditions and a community-driven incentive to get out and get after it; and the excellent photography of a curious aerial explorer named John Scurlock. Online access to quality winter photographs of Cascade peaks inspired a feverish period of first ascents — in at least one case a new route was done only a few days after Scurlock shared a photo of an unclimbed peak.

Like so many others, our climb started with a John Scurlock photo. The west side of Sloan had been climbed only a few years before but the line we spied on the SW face was, as far as we knew, unclimbed. Getting ready to charge off at something so uncertain felt audacious and exciting. So often in climbing the aspects of adventure are diminished by all the available information: how to get there, what gear you will need, how to get off the thing if you do manage to climb it, etcetera. It’s easy to say, “I just won’t look at it,” but it’s hard to actually do.

We had a USGS topographic map, an aerial photograph, and a weather history that said there would probably be a lot of frozen stuff on the mountain. This is much more than most of the pioneers of climbing history had, but it was still little enough to be exciting — embrace the uncertainty. We found the closest road to the SW face and drove it until we got the car stuck in the snow, strapped on skis once again and set off for what looked like on the map a reasonable camp.

Excitement trickled in as the SW face came into view, bathed in afternoon sun. “I think there’s gonna be something up there to climb,” I said to Marcus. Ribbons of ice threaded all over the face, and a quick contour revealed the line we spied in the photo: fat and continuous. Game on. We snapped some photos in the fading light and fell asleep stoked.

Waking up to the alpine start alarm is a tough thing to do. Usually, you’re being battered by wind in a tiny tent, curled in a sleeping bag and clinging to warmth. It’s cold and dark outside, and you have to open the tent and get snow everywhere while you stuff numb feet into frozen boots. Then comes digging around for the stove and the chilly task of melting snow for breakfast and water. Isobutane canister stoves are the most efficient but are fickle in altitude and cold. I’ve found the best bet for quick water in the morning is to sleep with the fuel canister in your sleeping bag. After digging ours out from between my thighs, melting snow for the day and shoveling our faces with butter and rice Marcus and I head off for the base of the route.

Once again we are thwarted by the weather forecast. Standing at the base of the route — which looks continuous and incredible — we’re battered by gusts of wind of the 50-mph-knock-you-on-your-ass variety. Dark clouds brood overhead. We decide to wait a bit, and discuss the objective hazards of rapping the route in the wind. Then, we scoot a little closer to the base of the first pitch and wait a little bit more.

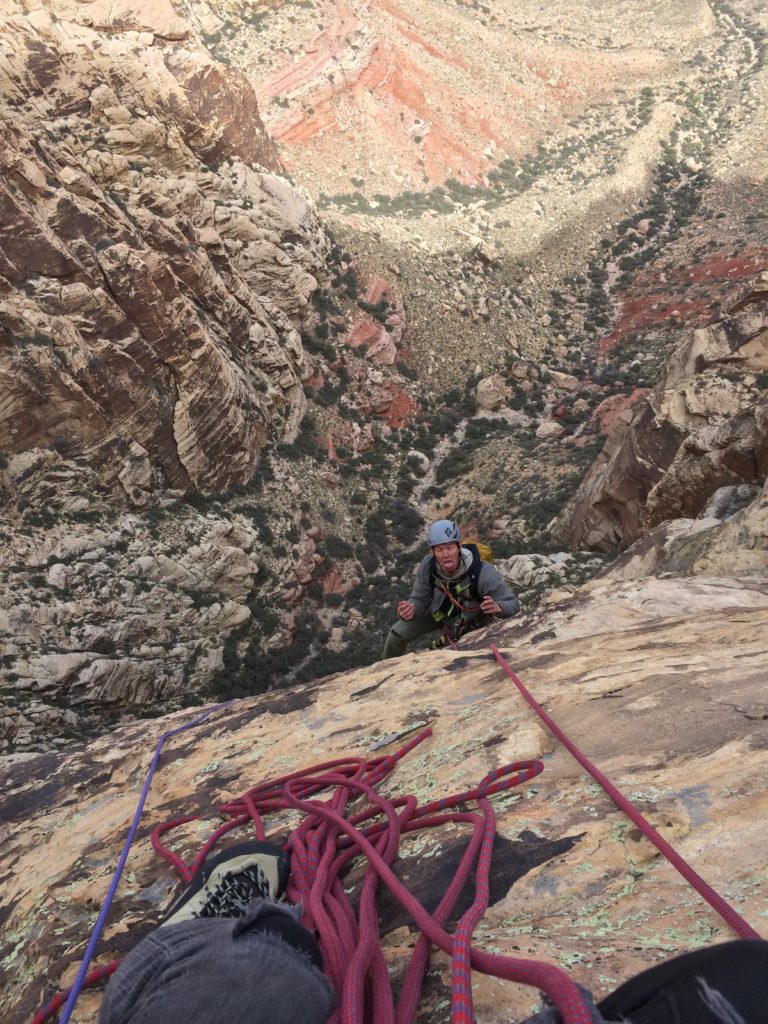

Finally, we trade a glance. The glance. Marcus pulls the gear out of his pack and starts racking up while I flake the rope: we’re giving it a shot. High velocity spendthrift pelts my exposed face as I blindly pay out slack to his indistinguishable form. Three excellent pitches later, Marcus retires the lead and hands me the rack, the first logical chunk of the climb over.

My lead is the first question mark of the climb, a traverse from the belay to a thin runnel of what looks like more of the good nevé we had seen lower on the route. This section leads into a meatier couloir, to another ledge traverse, to what looked like the money pitch of the climb: a long section of steep, blue ice.

Ten feet up with no pro, I gingerly swing a tool into the center of the narrow runnel. My pick slides easily through the unconsolidated snow-ice and bounces off the vertical rock beneath. A gust of wind threatens my stance and fills my nose with powder snow, and I say, “nope, nope, nope,” and down climb to the base of the pillar. The runnel of plastered snow ice is only a couple of body lengths long until turning back to hard nevé above, but sometimes that’s all it takes to shut you down. I scrape around for a few more minutes looking for another way up, but the only viable options look like heinous aid climbing.

It doesn’t take much to convince Marcus that’s it not going to go, especially not in these conditions, and we start rigging the first rappel. After getting down safely and packing up our camp, we stared wistfully up at the still-unclimbed line and awesome face above us. By definition a failure, but our most successful failure yet. The climbing was excellent, and the route almost went — our shutdown was primarily due to the brutal wind and threatening skies.

We skied to the car more psyched than ever. The mere act of daring to try something new felt like cracking a door into a new world, and capped off the learnings of the two week trip well.

Riles out.