“Campghanistan,” one of my climbing friends and Red Rock local called the particular patch of BLM land we inhabited for two weeks. “The worst campground you’ll ever pay money for,” the rest of the climbers we met in the next few months would call it. We’re right outside Las Vegas, Nevada, climbing at a mecca for long traditional rock climbing: Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area. Only 15 miles outside of Vegas and visible from the strip, almost 200,000 acres of public conservation land house a set of red rock formations called the Keystone Thrust. The walls are steep and as high as 3,000 feet. In short, it is awesome.

Lying shirtless in my underwear on a concrete slab, our neighbor from the campsite next to ours approaches me and launches into the introductory conversation typical among climbers: What did you climb today, what’s on your tick-list, et cetera. Except when my part of the conversation is over, the guy doesn’t stop. He goes on a veritable rampage of his most recent climbing accomplishments and future goals. In climbing culture, “spray” is a derogatory term for the unwanted monologue of climbing accomplishments or route information.

Thus our neighbor earned the name, “Spraylord.” Forever more he shall be known. Spraylord was a constant presence in the rest of our two weeks in Campghanistan, and his nightly monologues about climbing adventures with a colorful cast of cohorts became a reliable source of entertainment and an integral part of our Red Rock experience.

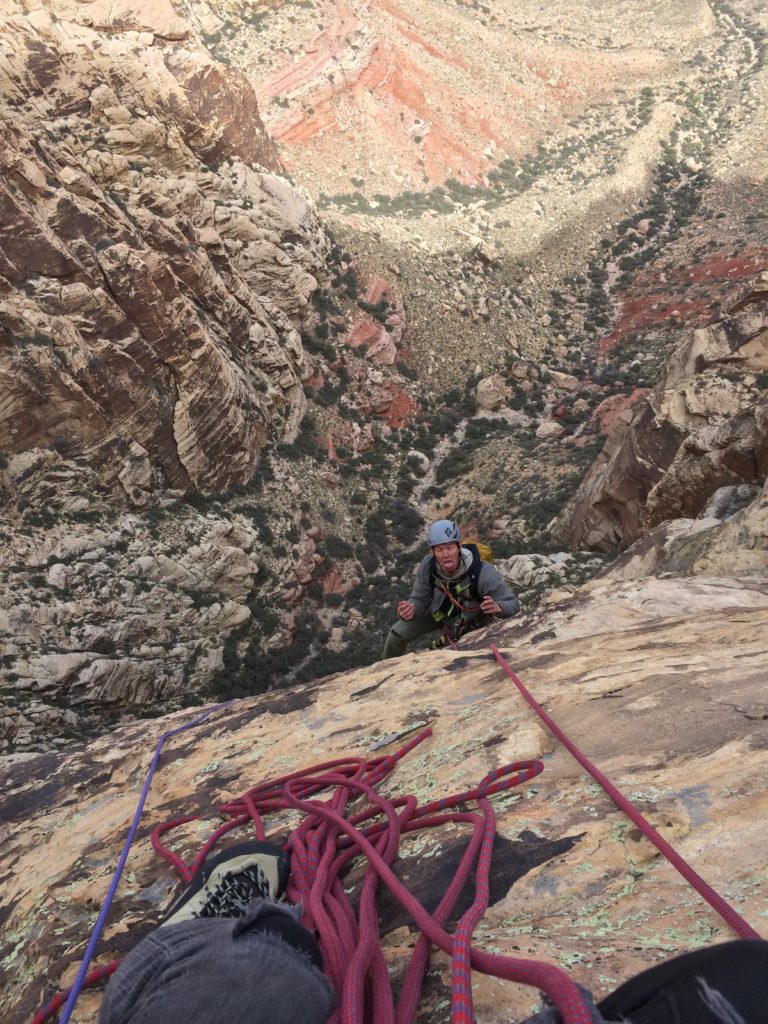

After a week of personal ventures, Marcus and I are joined on our particular slab of concrete in the desert by a posse from the Yale Climbing Team. We ticked off some classic, fun lines like Triassic Sands and set off on some more adventurous experiences like a topout of Dream of Wild Turkeys and a linkup of Inti Watana and the top of Resolution Arete. On the approach to the latter climb we made some new friends in the dark hours of the morning in the Nevada desert, which you can read about here.

Despite our best efforts to convince new members of the climbing team that trad is indeed, rad, we only got a few of them to tag along on multipitches. But by the end of our tenure in Campghanistan we had a couple more climbers leading on gear and the assurance that the stoke would spread, eventually. What work we could do was done.

After a few weeks our friends hopped planes to return to that former life of academic rigor and the competition for concrete slabs in the BLM campground became fierce. The dates for the Red Rock Rendezvous loomed — an event for climbers that “celebrates the climbing life,” but meant intolerable crowds for the grumpy-old-trad-guy attitude that Marcus and I had developed. We agreed that while there was much yet to do, it was time to move on.

—-

Where is there to go but further into the desert? The next stop on our tour of international climbing destinations was Indian Creek, Utah. We framed this entire trip around the idea of collecting skills for the mountains. Get comfortable on steep ice in Ouray, get fast on long rock routes at Red Rock, build crack climbing competency at Indian Creek.

I feel pretty soft leading with a double rack of Camalots on a route that was put up on hexes in the ’70s. The hardmen and hardwomen who established all the hard routes here bemoan the magazine cover shoots and incoming crowds of gym climbers like me, but they’ve got the right to complain. And there’s a reason for all the people — it really is an incredible training ground. We learned more about crack technique here in a few weeks than we could have in months anywhere else.

“I dunno, man. We might be staying somewhere else.” A flowing creek has rudely interrupted the dirt road that leads to our intended stay at the Bridger Jack BLM campsites. Plastic chunks of passenger cars litter both sides of the stream crossing; casualties of the low-clearance vehicle. I feel underneath my Subaru, guessing at how tall a rock would have to be to knock the oil pan off. I pop the hood and check the intake, guessing at how deep the front end could go underwater before the engine started sucking H20 into the cylinders instead of gasoline.

“Nah.” Shrug. “Should be fine. Let’s hit it.” I guess at a shallow line through the creek, rev it high in 1st, and plunge in. I cringe when a wave of water laps on top of the hood, but the car breaches the opposite bank with nary a choke. The rest of the road into the camping area makes every attempt to destroy the suspension on my car, but we arrive in our new kingdom in functional form. Flat rocks stacked into chairs and tables greet us. Our neighbors are distant, and the beautiful Bridger Jack buttress dominates the skyline. There’s no bathroom, but this sure beats the hell out of Campghanistan.

We developed a fascination for our new neighbors. There was a large vinyl sticker on their car roof-box of a giant mustache and a hashtag slogan something to the effect of, “Mustache Crew,” and they lived up to the sticker hype. Our first sighting of the human occupants of the Mustache Crew car revealed five dudes, heavily sporting their vinyl namesake. We were duly intimidated. “Dude. I bet those guys are crushers,” Marcus said.

If face climbing is like dancing — delicate, precise, controlled — crack climbing is like boxing. It’s abusive and often desperate. You squash, shove, and torque appendages. You pull hard just to stay in place, and pull harder to gain precious vertical inches. We were disappointed in ourselves when we first counted how many pitches we were climbing in a day as it was half of what we would get done on a typical cragging day. Crack climbing is work, and we got worked.

Returning to the now-fond Bridger Jack campground one afternoon after a rest day in Moab, we found that a recent windstorm had wreaked destruction on our neighboring campers. The trusty Coleman tent I unearthed from the family closet employed its usual (and highly effective) tactic of jettisoning all support poles and lying flat. The Mustache Crew, with un-staked tents of higher quality, were not so lucky. Of the five tents we counted originally in their site we now saw one, tangled upside down in a nearby bush. Of the others we saw only hints: a headlamp in the road, bits of clothing strewn here and there, a backpack twenty yards off.

Lots of yelling heralded their return. After their initial shock, we helped them stumble through the desert to pull socks off of tree branches and tents out of drainages. Along with most other people in the Bridger Jack BLM campsites, they packed up and left shortly after, the vinyl mustache on their roof-box now a symbol of shame. We decided that maybe they weren’t crushers after all.

Our taste of desert climbing ended with a whipper. We made the mistake of planning out our next destination — alpine climbing in the Sierra — on one of our rest days, and got too excited about leaving. I promised myself one last redpoint effort on a harder climb, and three feet from clipping the anchors I melted out of a cupped hand-jam with the rope behind my leg and fell twenty feet upside-down. “Uh. I think we should just go to California, dude,” I said after righting myself. And we did, that same afternoon.

Leave a Reply